“Long time ago the Dena’ina did not have songs and stories. Then came the time that Crow sang for them. Till then, as they worked together and traveled, they chanted di ya du hu to keep them in time. Peter Kalifornsky, “Crow Story” From the First Beginning, When the Animals Were Talking

Artist’s Proof Editions has just opened its first crowd-funder, the Kalifornsky Project on Indiegogo. I’ve got more to tell you, here, but, from the beginning, if you think it worth supporting, Artist’s Proof and I will be very grateful for your donation.

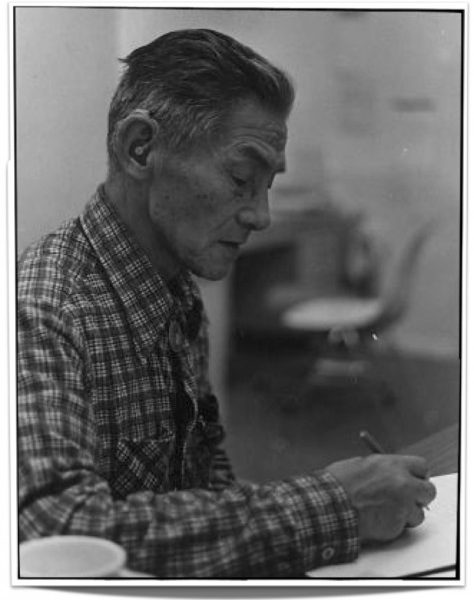

Peter Kalifornsky (1911-1993) was the first writer and the last native speaker of his dialect of Dena’ina, an Alaskan Athabaskan language. For his Dena’ina texts he was praised as a literary stylist. He was also an intellectual, who, with his theory of writing and meaning, preserved his native language, adapting the writing system he was given to the intrinsic patterns of his tongue. He was the author of traditional stories, essays, songs, word lists, commentaries. But he wanted to tell us more: the“back story,” he called it, a way of knowing the world, the visible and the invisible, which is rich, profound, demanding. Yet, he knew he would never write it, in either Dena’ina or English. He asked for a secretary.

I was an itinerant poet and an independent scholar and had lived in Athabaskan country for some years. I became his secretary.

At some time during the early 1980s, I was given a book of stories by this writer, Peter Kalifornsky, who, through his language, was related to people in whose village I had lived for a while. I was told that he was of the stature of, for example, Amos Tutuola. The stories were in Dena’ina and English, though not in fluent translations. But you could tell that this was a writer, in every sense we know the word.

One story caught my attention and then began to live with me, the “Crow Story,” about how Crow—the great Raven; they would not name a powerful creature directly—gave the first songs and stories to the People Who Sit Around the Campfire. It is a funny, clever story full of wonders. What did it mean? I thought I saw something in it, but wanted to ask the author if I had got it right.

Peter Kalifornsky was a charming host, pleased that a visitor wanted to talk about meaning. He persuaded me to return, with pen and paper in hand. For five years, I returned, again and again, with pen and paper in hand. I listened; I wrote; I asked questions; I wrote, until he joked about my “little hand making chicken scratches.” And so we went on, until by 1988, I had hundreds of pages of our translations of his stories—and of all the new stories he had written since we began talking—and of our conversations, linked by footnotes to his texts. It was an impossible manuscript.

And then he died, in 1993. Time passed. About six years ago, I returned to the task: how to prepare this manuscript for publication. I opened the box it had lain in for nearly twenty years and found (how could I have forgotten) not only the 800+ manuscript, but also: cassette tapes, for Peter Kalifornsky had recorded himself reading in Dena’ina so that we would always know how to pronounce his tongue. A Xeroxed copy of his own manuscript, also given to me. Annotated copies of his earlier publications. My hand-written field notes. Other memorabilia. None of it digitized. How to turn this glorious collection into—a book? A digital archive? A what-to-make-of-this?

And here came the iPad, and here came Apple’s free application for making books, the iBooks Author. And here came, suddenly, a sense of possibility: I could take all this beautiful material, digitize it carefully, and put it on the iPad. And Peter Kalifornsky’s people—the rest of us, too, for he did not exclude us, but welcomed us into his language—could hold his knowledge in their hands. They could read, they could hear his voice, they could examine scanned copies of his manuscript pages. They could learn what he had wanted to tell them. “They lived life through Imagination,” he said of the Old Dena’ina, “the power of the mind.”

As we all can read and listen and imagine. At Artist’s Proof, I’ve published the first of the four volumes of his writings, our conversations, his digitized sound files, images of his manuscript, notes. Three more volumes will follow (I update Vol. 1 periodically), till the work he entrusted to me is completed, and I can take it home.

- Vol. 1, From the First Beginning, When the Animals Were Talking: the Animal Stories

- Vol. 2, From the Believing Time, When They Tested for the Truth

- Vol. 3, From the Time of Law and Education

- Vol. 4, From the Time When Things Have Been Happening to the People (“the last two or three thousand years!”)

Please join me in this enormous, thrilling work. Welcome. Thank you.