The poet Samuel Menashe died a little more than three years ago, on August 26, 2011. I hadn’t seen him in a while. We were introduced at a writers’ party on the Upper West Side and discovered our mutual interest in Hubert Butler. We had both visited Maidenhall; we knew a number of Irish people in common; and he, who was much older than I, had met Hubert and Peggy Butler. Some thought he was Irish, as he went there often, and poems of his were published there and published well. He began reciting, beautifully, in his cantorial baritone.

O Lady lonely as a stone

Even here moss has grown.

I used to visit him when I still went to New York. Once he took me to lunch — was it? or to supper? or for a glass of wine?; or, I invited him — to the Boathouse, in Central Park. He was courtly, with worn collar and cuffs, white hair curling over his collar, just a bit disheveled. He pointed out to me the gondolier, who swept his long boat hopefully to our water-side table, then floated away as Samuel began telling his poems.

He gave me six poems for Archipelago, from The Niche Narrows.

The Offering

Flowers, not bread

Cast upon the water—

The dead outlast

Whatever we offer

Several years later, I asked him for more. He promised some wonderful poems which he said were variations on poems about to appear, or on old poems. Instead he sent a war story. He was 19 when he went for a soldier, in 1943, and his best friend died. He fought at the Battle of the Bulge.

Today, for a while, I wished that I had died instead of him because I think that his life would have been better than mine now is — though I have all my limbs and my senses. Two months ago, I was thirty and I am still in pretty good form — I am just beginning to wrinkle around the eyes — but as I once said to myself with sudden sententious knowledge, a young man who go[es] to war should die. Don’t try to make me defend this statement. Either one knows it for oneself or one does not know it. I think it tells the truth but not for everyone. (“Well Everyone Must Die and Today Was the 11th of December”)

“In 1950,” he wrote, “I presented a thesis at the Sorbonne called Un essai sur l’éxperience poetique (étude introspective). By poetic experience, I meant that awareness which is the source of poetry. I had been a biochemistry major before enlisting. Although I was well read for my age, the only literary influences on my word so far as I can tell were the short poems of William Blake and the English translations of the Hebrew Bible. ‘The still small voice’ of Elijah was my article of faith.”

He did send me more poems, later, and was pleased by the title I suggested for them: Eyes Open to Praise, from “Hallelujah.” He said, “You’ve understood my work well. It is one of the most important lines I’ve ever written. Indeed, it’s pre-speech in its meaning, isn’t it?” I can almost hear his joyous laugh. He was a joyful man. I wonder if his joy was not a true act of perfect will.

His first language was Yiddish; his second, English, at age 5; his third, French, age 11. He loved his mother and father; his poems about them are affecting.

Stephen Spender: “Samuel Menashe is a poet of entirely Jewish consciousness, though on a scale almost minuscule. He is not one of the prophets, concerned with exodus, exile, and lamentation: but he is certainly a witness to the sacredness of the nation in all circumstances in life and in death. His poetry constantly reminds me of some kind of Biblical instrument — tabor or jubal — and the note it strikes is always positive and even joyous. His scale is, I repeat, very small, but he can compress an attitude to life that has an immense history into three lines.”

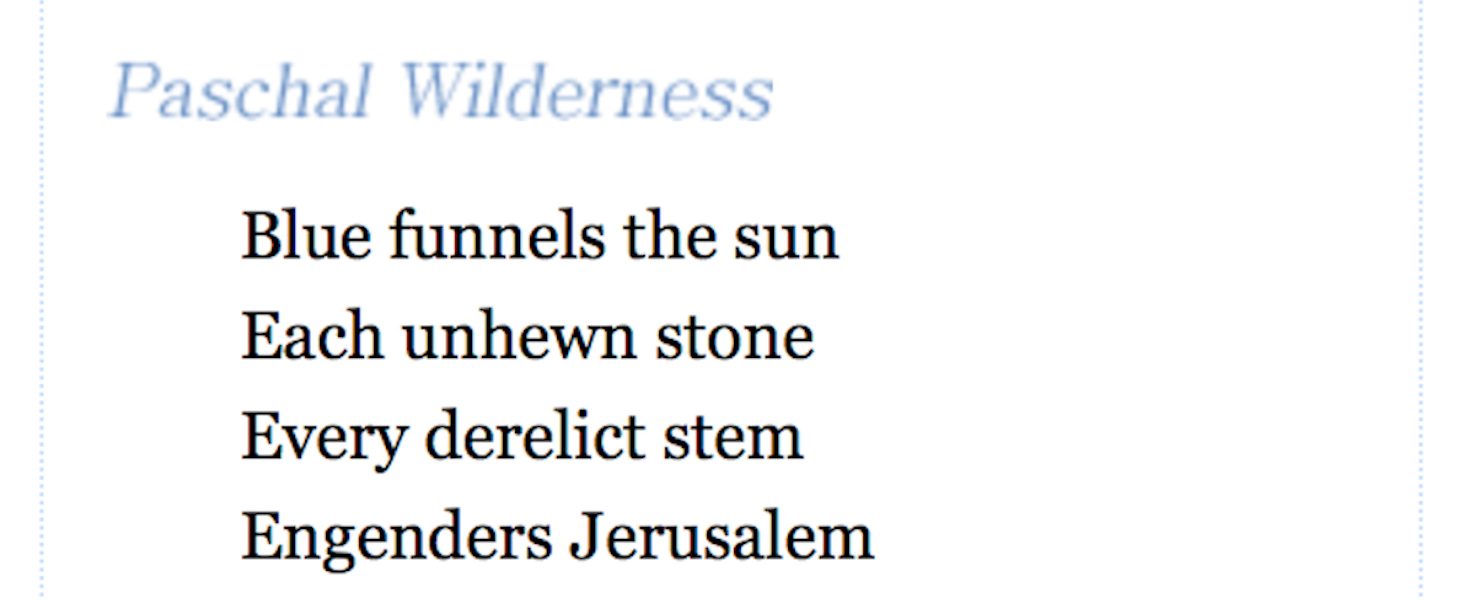

He was never given to length. His work unaccountably was not more widely known in this country, though it was brilliantly published in England and Ireland; but it is known by the best of serious poets. He won the Pegasus Prize “Neglected Masters” awarded by the Poetry Foundation. As part of the award, his Selected Poems was published, with an introduction by Christopher Ricks, by the Library of America in Autumn 2005. The composer Otto Leunig drew the text of his cantata No Jerusalem But This from two collections by Samuel, The Many Named Beloved and No Jerusalem But This, which included the poems I put in Archipelago. Between 2005 and 2010, the composer Ben Yarmolinsky set 37 of Samuel’s poems to music, for solo voice with accompaniment.

There is a little video of Samuel in his small apartment on Thompson Street. He is telling his poems, as he loved to do. A friend wrote me after seeing it, “I could describe every decayed, cluttered corner, crack in ceiling, desk, layering on bathtub board. Terrifying to think of living that way but he wears it all like his comfortable grey suit. I wonder if he was an Orthodox Jew, who seem to feel that cleanliness is unholy, and yet there are volumes in the bible on cleanness.”

I am so happy remembering him.

Hallelujah

Eyes open to praise

The play of light

Upon the ceiling—

While still abed raise

The roof this morning

Rejoice as you please

Your Maker who made

This day while you slept,

Who gives grace and ease,

Whose promise is kept.

For further reading:

Samuel Menashe: New and Selected Poems, Expanded Edition. Christopher Ricks, ed. iBooks

Eyes Open to Praise, Archipelago, Vol. 8, No. 4

Six Poems, Archipelago, Vol. 5, No. 2

Library of America American Poets Project

Ben Yarmolinsky, Setting Samuel Menashe’s poetry to music